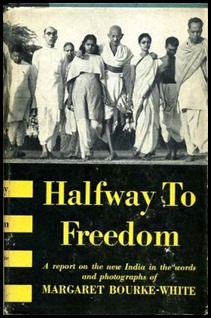

Halfway to Freedom: A Report on the New India

Authoress: Margaret Bourke-White

Publisher: Simon & Schuster

--------------------------

~ Direct Action in Calcutta

Why had the fearful Great Migration come to pass? Why were millions of people wrenched from their ancestral homes and driven toward an unknown, often unwanted "Promised Land"? For years Hindus and Muslims had struggled side by side for independence from British rule. With freedom finally on the horizon why should India begin to tear herself in two along religious lines?

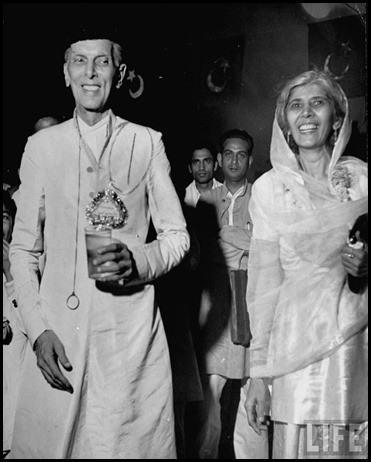

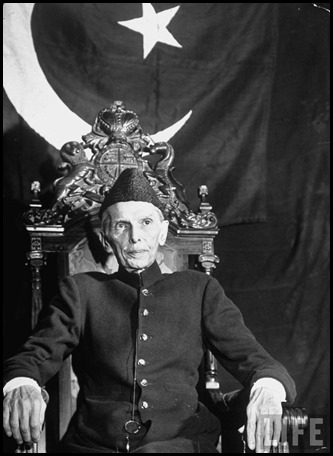

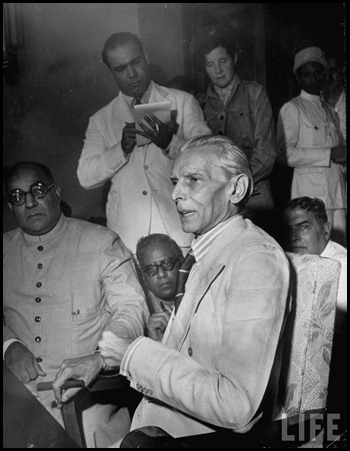

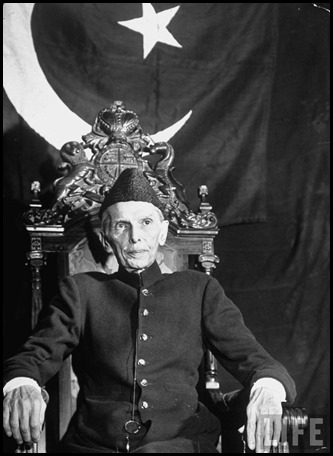

The overt act that split India began in the streets of Calcutta. But the decision was made in Bombay. It was a one-man decision, and the man who made it was cool, calculating, unreligious. This determination to establish a separate Islamic state came not -- one might have expected -- from some Muslim divine in archaic robes and flowing beard, but from a thoroughly Westernized, English-educated attorney-at-law with a clean-shaven face and razor-sharp mind. Mahomed Ali Jinnah, leader of the Muslim League and the architect of Pakistan, had for many years worked at the side of Nehru and Gandhi for a free, united India, until in the evening of his life he broke with his past to achieve a separate Pakistan.

Jinnah lived to see himself ruler of the world's largest Islamic nation before he died in September, 1948, at the age of seventy-two, but I think of him as reaching his pinnacle of power two years before his death, when freedom-with-unity appeared on the verge of becoming a reality and he took the momentous steps that crushed all hopes for a united India.

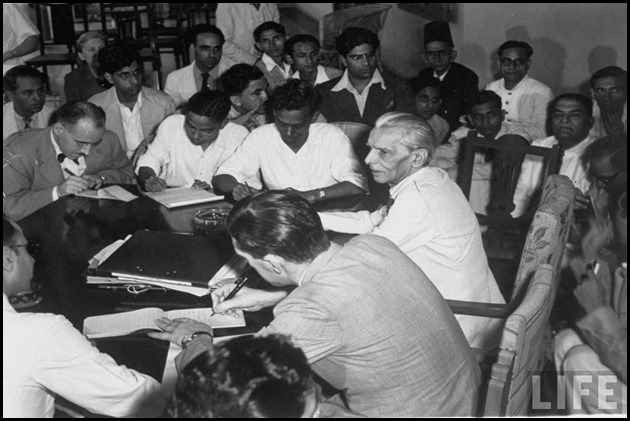

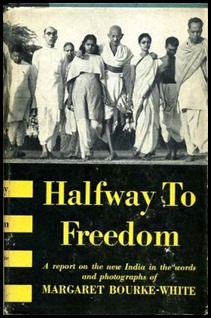

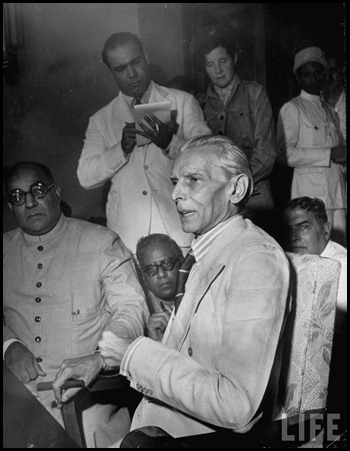

Jinnah's press conference at his Bombay home on fashionable Malabar Hill, in late July, 1946, marked the public turning point. It was so unusual for the Quaid-i-Azam, or "Great Leader," to call a press conference that both foreign and Indian reporters rushed eagerly to attend it. Nor were they disappointed. On that mid-summer morning, Jinnah intimated -- rather boldly -- the coming of Direct Action Day. Two and one half weeks later this day touched off a chain of events that led, after twelve explosive months, to a divided India and the violent disruptions of the Great Migration.

Until then most of us had thought the differences between the Congress Party and the Muslim League would somehow be resolved and that freedom would bring a united nation. Jinnah's arguments for division were all familiar: that the Muslims in India were outnumbered three to one by Hindus and would be crushed under Hindu domination; that Hindus worshiped the cow while Muslims ate the cow; that religion, customs, culture all made Muslims different from Hindus. Opponents of the two-nation theory maintained that Hindus and Muslims could not be so different, since there was no racial difference. Ninety-five per cent of India's Muslims were just converted Hindus. Even Mr. Jinnah, they were fond of pointing out, had a Hindu grandfather.

For my part, I believe that the tragic weakness of the Indian leaders during this crucial period was their failure to take a firm stand against the forces of Indian feudalism. A spellbinder with slogans found it all too easy to galvanize the pent-up suffering of centuries into one powerful current of religious hatred. That this was done by an ambitious lawyer in Western dress and of unorthodox habits makes it all the clearer that religion was used like a document plucked from a briefcase.

There was a good deal of the successful lawyer about Jinnah that midsummer morning of the press conference, as he stood on the steps of his spacious veranda receiving the reporters. A pencil-thin monochrome in gray and silver, with perfectly tailored suit and tie and socks precisely matching his hair, his manner with us was courteous but formal. As he fitted his monocle to his eye and began to speak, there was something consciously theatrical about Mr. Jinnah -- throwback perhaps to that most un-Islamic chapter of his past when he was a Shakespearean actor in England.

His statement to the press was in the form of a monologue, delivered in an icy voice, which was forecast of fiery events to come. "We are preparing to launch a struggle. We have chalked a plan." We reporters, although we sat around Jinnah in a closed circle, had almost to stop our breathing to hear his curiously hushed words. He had decided to boycott the Constituent Assembly. He was rejecting in its entirety the British plan for transfer of power to an interim government which would combine both the League and the Congress. He lashed out against the "Hindu-dominated Congress" in his flat, chilled monotone. It seemed clear, now the bondage to the British was drawing to an end, that he was free to concentrate all his fire against the opposite party.

"We are forced in our own self-protection to abandon constitutional methods." His thin lips slit into a frigid smile. "The decision we have taken is a very grave one." If the Muslims were not granted their separate Pakistan they would launch "direct action." The phrase caught all of us. What form would direct action take, we all wanted to know. "Go to the Congress and ask them their plans," Mr. Jinnah snapped. "When they take you into their confidence I will take you into mine."

There was silence for a moment, broken only by the cooing of pigeons, hopping over Jinnah's manicured lawn. Then he added in the same toneless voice, so strangely unmatched to his words: "Why do you expect me alone to sit with folded hands? I also am going to make trouble."

Next day the Quaid-i-Azam changed out of his double-breasted suit and put on Muslim dress and fez for the Muslim masses. Standing on a platform liberally decorated with enlargements of his portrait, he announced that the sixteenth of August, two and a half weeks hence, would be "Direct Action Day." His vituperation against the Congress was acidly explicit. "If you want peace, we do not want war," he declared. "If you want war we accept your offer unhesitatingly. We will either have a divided India or a destroyed India." And the Muslim Leaguers jumped up on their seats and tossed their fezzes in the air.

It was a battle between top-flight politicians now. The papers blazed with accusations from both sides -- League and Congress equally intolerant in their attacks. The opposing streams of fiery words had a terrible effect on the emotional Indian people. Passions mounted during the crucial fortnight; Direct Action Day dawned in an atmosphere of dread and foreboding.

Most of what I learned about that day came from a little tea-shop keeper in Calcutta, where the explosion began. As soon as I heard of the incredible events taking place, I had flown from Bombay to Calcutta. The disruption of normal city life was so great that it was some time before I could make my way to the ruined heart of the bazaar district. Hunting for a survivor who had been an eyewitness to the first stroke of direct action, I found Nanda Lal, in the wreckage of his teashop. ........

![Men adding wood & straw to funeral pyres in preparation for cremation of many corpses after bloody rioting between Hindus and Muslims[4] Men adding wood & straw to funeral pyres in preparation for cremation of many corpses after bloody rioting between Hindus and Muslims[4]](http://lh3.ggpht.com/-brHZS2b7DdU/USczKOHD_wI/AAAAAAAAC5Q/MBq8NOeNl_I/Men%252520adding%252520wood%252520%252526%252520straw%252520to%252520funeral%252520pyres%252520in%252520preparation%252520for%252520cremation%252520of%252520many%252520corpses%252520after%252520bloody%252520rioting%252520between%252520Hindus%252520and%252520Muslims%25255B4%25255D_thumb%25255B4%25255D.jpg?imgmax=800)

On the morning of August 16th, Nanda Lal started his oven and set out his tray of sweetmeats as usual. When his little son came out with the jars of mango pickle and chutney, he commented to the child that the streets looked reassuringly quiet. The sacred cows that roam freely through the thoroughfares of Calcutta were sleeping as usual in the middle of the car tracks, and rose to their feet reluctantly, as they always did, when the first streetcar of the day clanged down Harrison Road.

It was the sight of that first tram that confirmed Nanda Lal's fears that this day was to be unlike all other days. Normally it was so crowded with commuters that they bulged from the platform and clung to the doorsteps and back of the car. Today there was hardly a passenger on board.

Then things began happening so quickly that Nanda Lal could hardly recall them in sequence. But he did remember quite clearly the seven lorries that came thundering down Harrison Road. Men armed with brickbats and bottles began leaping out of the lorries -- Muslim "goondas," or gangsters, Nanda Lal decided, since they immediately fell to tearing up Hindu shops. Some rushed into the furniture store next to the Happy Home and began tossing mattresses and furniture into the street. Others ran toward the Bengal Cabin, but Nanda Lal was fastening up the blinds by now, shouting to his son to run back into the house, straining to bar the windows and close the door. .......

During the terrible days that followed, Nanda Lal huddled with his family and relatives in the upper hallway. Sometimes bricks and stones crashed through the windows of the outside rooms. The children cried a great deal; they were hungry as well as terrified. .......

On the fourth day Nanda Lal noted that the weapons in the street fighting had grown heavier. Soda-water bottles had given way to iron staves, and unfortunately the neighborhood had a plentiful supply of rails from the fence surrounding the near-by Shraddhananda Park. Finally, as the skirmish of the iron pikes reached its fiercest, a convoy of three military tanks rolled through and machine-gunned the mobs, and along with them the police made their belated appearance. ......

![Vultures feeding on corpses lying abandoned in alleyway after bloody rioting between Hindus and Muslims[5] Vultures feeding on corpses lying abandoned in alleyway after bloody rioting between Hindus and Muslims[5]](http://lh4.ggpht.com/-BcjMH2AKT7k/USczWluqwkI/AAAAAAAAC5g/TUdrpUQXS_Y/Vultures%252520feeding%252520on%252520corpses%252520lying%252520abandoned%252520in%252520alleyway%252520after%252520bloody%252520rioting%252520between%252520Hindus%252520and%252520Muslims%25255B5%25255D_thumb%25255B4%25255D.jpg?imgmax=800)

When peace returned to Calcutta on the fifth day, the streets were a rubble of broken bricks and bottles, bloated remains of cows, and charred wrecks of automobiles and victorias rising above the strewn figures of the dead. The human toll had reached six thousand according to official count, and sixteen thousand according to unofficial sources. In this great city, as large as Detroit, vast areas were dark with ruin and black with the wings of vultures that hovered impartially over the Hindu and Muslim dead.

Thousands began fleeing Calcutta. For days the bridge over the Hooghly River, one of the longest steel spans in the world, was a one-way current of men, women, children, and domestic animals, headed toward the Howrah railroad station. ......

![Evacuees streaming across the Howrah Bridge on their way to the railway station in hopes of escaping the city after bloody rioting between Hindus and Muslims[3] Evacuees streaming across the Howrah Bridge on their way to the railway station in hopes of escaping the city after bloody rioting between Hindus and Muslims[3]](http://lh3.ggpht.com/-nsG8J5lsxlI/USczfdBKwFI/AAAAAAAAC5w/lr7Cjf_rlWM/Evacuees%252520streaming%252520across%252520the%252520%25255B8%25255D.jpg?imgmax=800)

But fast as the refugees fled, they could not keep ahead of the swiftly spreading tide of disaster. Calcutta was only the beginning of a chain reaction of riot, counter-riot, and reprisal which stormed through India for an entire year.

The next link in the chain was the Noakhali area in southeastern Bengal. Here in the uncharted recesses of swampy lowlands and hyacinth-choked bayous I talked with Hindus who had abandoned their villages en masse and fled to the riverbanks. They had strange tales to tell of forced conversion to Islam, of being compelled to throw the images of their gods into the water and to eat the meat of the sacred cow. ......

Gandhi -- though he was far too old to endure such hardship -- went to Noakhali and tramped on foot through marshes and jungle trying to restore confidence to the villagers. Trade-unions and peasant organizations threw their weight toward unity. It is significant that throughout the worst of the disruption in Bengal, five million Hindu and Muslim sharecroppers campaigned together in the Tebhaga movement for long-overdue land reforms. Wherever there was constructive leadership toward some goal of social betterment, religious strife dwindled to the vanishing point.

But between these small islands of Hindu-Muslim cooperation were the burning villages, the blazing fanaticisms. The sparks of Bengal flew westward to the state of Bihar, where Hindus wreaked merciless vengeance on the Muslim minority. The flames of Bihar fanned out to the Punjab and touched off explosions that dwarfed even the Calcutta riots.

Months of violence sharpened the divisions, highlighted Jinnah's arguments, achieved partition. On August 15,1947, exactly one day less than a year after Nanda Lal had seen direct action break out on his doorstep, a bleeding Pakistan was carved out of the body of a bleeding India.

------------------

~ The Great Migration

![People waiting in railroad station trying to escape city after bloody rioting between Hindus and Muslims[3] People waiting in railroad station trying to escape city after bloody rioting between Hindus and Muslims[3]](http://lh4.ggpht.com/-LLicq8cfbrA/USczoqn2uLI/AAAAAAAAC6A/3svHpcgYdCE/People%252520waiting%252520in%252520railroad%252520station%252520trying%252520to%252520escape%252520city%252520after%252520bloody%252520rioting%252520between%252520Hindus%252520and%252520Muslims%25255B3%25255D_thumb%25255B5%25255D.jpg?imgmax=800)

With the coming of independence to India, the world had the chance to watch a most rare event in the history of nations: the birth of twins. It was a birth accompanied by strife and suffering, but I consider myself fortunate to have witnessed and been able to document the historic early days of these two nations: India and Pakistan.

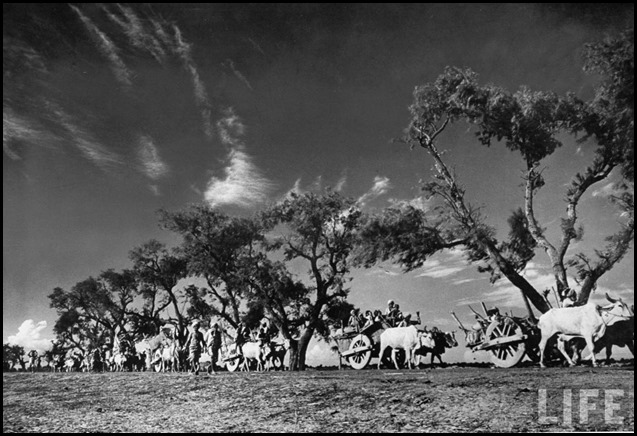

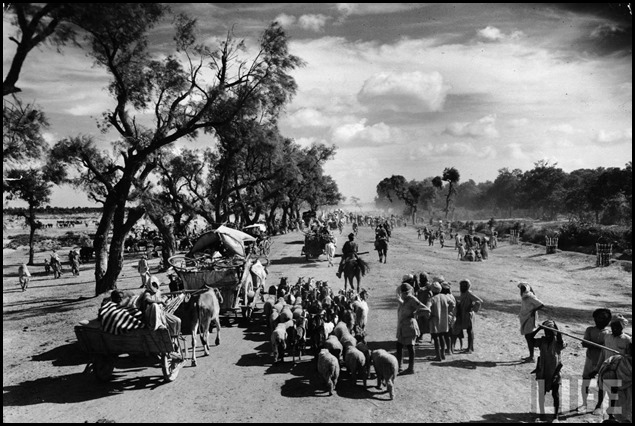

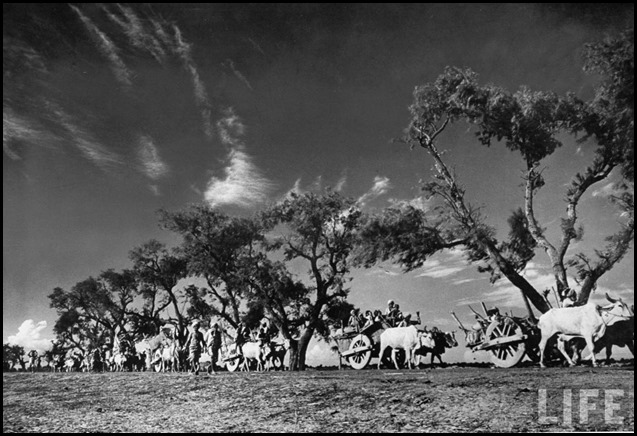

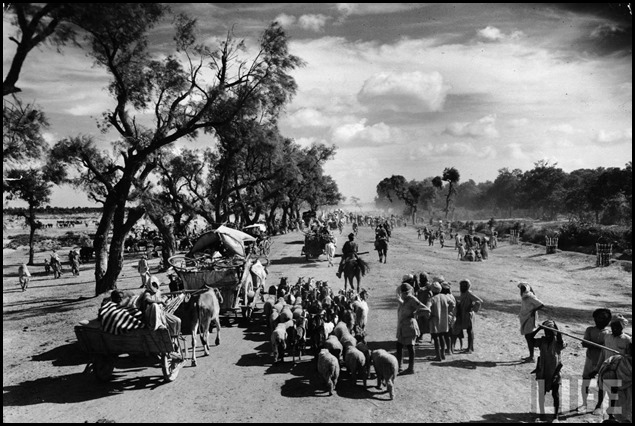

When I went to the Punjab area, in the North of India, in the fall of 1947 to begin photographing the newborn sovereign states, massive exchange of populations was under way. The roads connecting the Union of India with Pakistan looked as our Pulaski Skyway or Sunset Boulevard looks during the rush hour. But instead of the two-way stream of motorcars there were endless convoys of bullock carts, women on donkey back, men on foot carrying on their shoulders the very young or the very old.

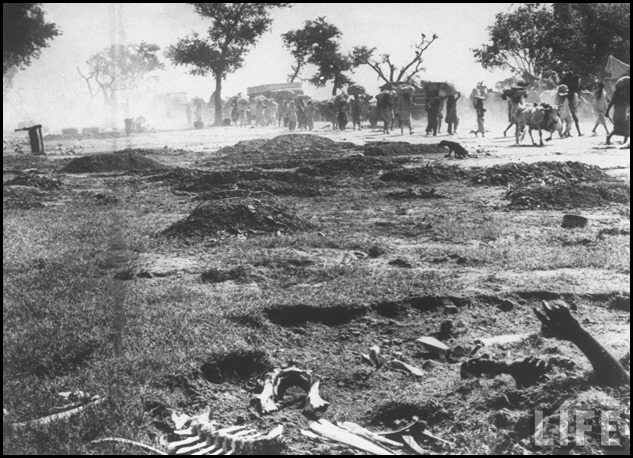

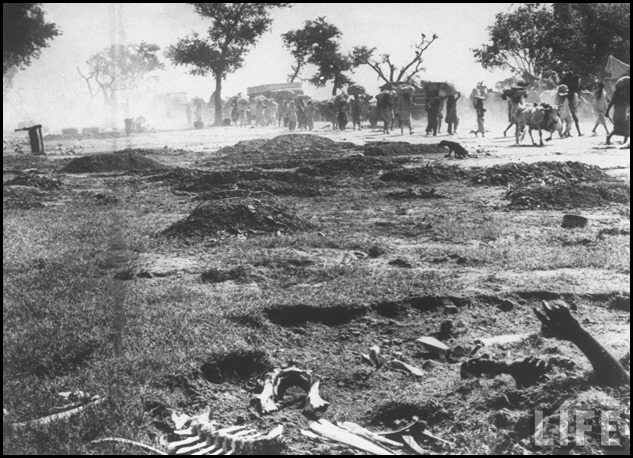

Babies were born along the way. People died along the way. Some died of cholera, some from the attacks of hostile religious communities. But many of them simply dropped out of line from sheer weariness and sat by the roadside to wait patiently for death. Sometimes I saw children pulling at the arms and hands of a parent or grandparents, unable to comprehend that those arms would never be able to carry them again. The name "Pakistan" means Land of the Pure: many of the pure never got there. The way to their Promised Land was lined with graves.

The hoofs of countless cattle raised such continuous columns of dust that a pillar of a cloud trailed the convoys by day. And in the evenings when the wayfarers camped by tens of thousands along the roadsides, and built their little fires and made their chapatties -- good deal, I suppose, like the unleavened bread of the Bible -- the light of their campfires rose into the dust-filled air until it seemed as if a pillar of fire hung over them at night.

Indeed, there was such a Biblical atmosphere about this mammoth two-way exodus that I turned to the Old Testament to compare its size with the migration of the Israelites. I found that the Children of Israel numbered eight hundred thousand, but since the Book of Exodus counted men only, this number would have to be tripled or quadrupled. Even so, the exodus of the Children of Israel was dwarfed by the great migration of Muslims, Sikhs, and Hindus which took place upon the partition of India. At the time that I was photographing it for Life magazine there were five million people on the move, with several more million due to follow as soon as room could be found for them. This, for these wretched millions, was the first bitter fruit of independence. ......

They flowed in a two-way stream across the border. Into the Indian Union came the Hindus and Sikhs . ; the Muslims poured into their new Pakistan, which they looked on as their Promised Land. All were led by fear, by highly questionable leadership, by ever dwindling hope. What had been merely arbitrarily drawn areas on a map began emptying and refilling with human beings -- neatly separated into so-called "opposite" religious communities -- as children's crayons fill in an outline map in geography class. But this was no child's play. This was a massive exercise in human misery.

As though the travail of a people divided by pen strokes was not great enough, North India, in this year of all years, suffered the worst floods since 1900. In the Punjab, which means Land of Five Rivers, all five began overflowing their banks, tearing away the earth barriers in the network of canals, spilling into the fields, and trapping entire encampments of refugees. I was almost caught myself in the rising of the River Ravi. .......

Thousands of peasants less lucky than I were trapped -- they had no jeep, no one to warn them. The River Beas claimed the most victims. When the water began receding sufficiently for me to get to it, I photographed one meadow between the river and a railroad ramp where four thousand Muslims had gone in to camp for the night. Only one thousand had come out alive. That meadow was like a battlefield: carts overturned wildly, household goods and farm tools pressed into a mash of mud and wreckage. .......

More fearful than flood and starvation was the ever present threat of attack by hostile religious hordes along the way. Hatreds had been so whipped up by the political pressures which had divided the nations that a new morality had developed. All members of a different religious group were fair prey for loot and murder. Travel by train was still more dangerous than by road because of the ease with which a crowded refugee train could be switched off the main tracks and, while being shunted back and forth, attacked and looted. The railroad station in Amritsar was a place of dread for Muslims. Amritsar, the holy city of the Sikhs and therefore the center of an especially militant form of fanaticism, was the last big junction which Muslim refugee trains had to pass through before crossing into Pakistan. I remember visiting the frightfully littered railroad station after an attack which had cost the lives of a thousand Muslim refugees, and seeing a row of dignified-looking Sikhs, venerable in their long beards and wearing the bright blue turbans of the militant Akali sect, sitting cross-legged all along the platform. Each patriarchal figure held a long curved saber across his knees -- waiting quietly for the next train. The Muslims were not always the victims. Trainloads of Sikhs and Hindus emigrating to India had hours of equal dread when passing through Lahore, the last great rail junction before they escaped from Pakistan. Hindu-Sikh convoys on the Pakistan highroads were a constant temptation to Muslim raiders. .....

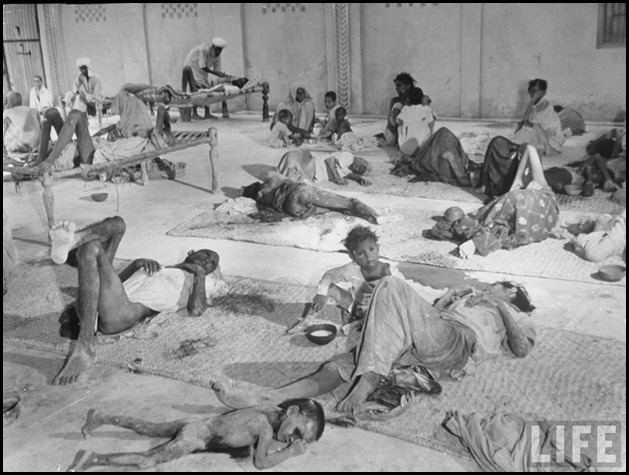

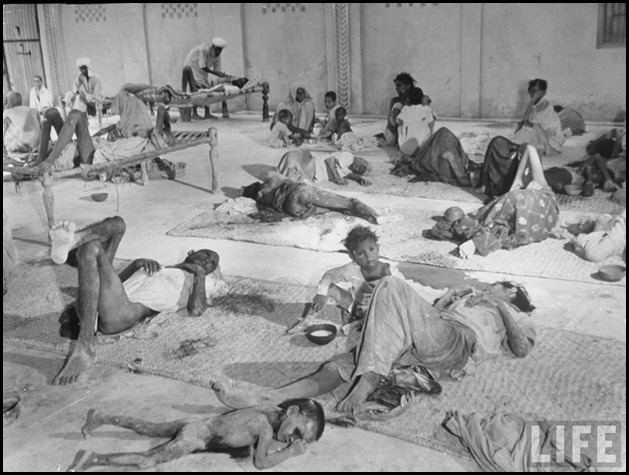

For the first time, Lee [a LIFE reporter] and I saw cholera; we had visited an improvised hospital in Kasur where I photographed eight hundred victims lying on the floor. Some, we were told, would pull through, although their appearance made us doubtful. Their lives depended partly on how much nourishment they had been able to get on the roads before the disease struck them down. The sight of these helpless sufferers had made me very angry. These were innocent peasants; some had been driven from their ancestral homes; the others had listened to the drumming of religious slogans and left home to pursue a dream.

Driving back to Lahore in the dusk, we suddenly saw the fields come alive, as though dragons' teeth had sprouted, with hordes of men carrying long poles mounted with knives. They were running forward, and as we rounded a bend in the road we came on a truckload of refugees, apparently Hindus ambushed in hostile Muslim territory. Already swarming figures had reached the top of the truck, throwing down bedrolls and other loot, while one of the attackers thrashed away with a hatchet. The screams were terifying. ....

Lee and I went on with the convoys week after week until our all our hair became stiff and gray with dust, our clothes felt like emery boards, my cameras became clogged with grit, and the endless procession of misery we were portraying seemed, as Lee described it, to be "wrapped in a horrible nightmarish gray lighting, where the heartbreaking sight of human suffering was mercifully blurred by our own physical weariness." But long after the last of my negatives and Lee's captions had been dispatched by air to Life, and Lee herself had flown to another part of the world on a new assignment, those millions of peasants were still trudging blindly forward on their tragic journey. The total of Sikhs and Hindu leaving Pakistan had reached four million, but with six millions Muslims coming in, this infant Land of the Pure seemed in danger of being swept away by the very numbers of the pure pouring into it. ....

Since the time of my first arrival in India a year and a half before Independence Day, I had watched the constant jockeying for position which had finally resulted in the creation not of a single, free, united nation but of these handicapped twins. I remember the many times when bloodshed had broken out during the preliminary sparring and the Pakistan promoters had said, "We must have our separate nation, or we will not have peace." But now that this separate nation had become a reality the people had not achieved peace. It was a little too soon to find out just what they had achieved.

---------------

~ The Messiah and The Promised Land

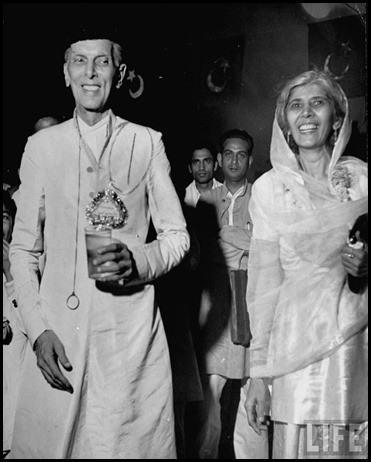

Pakistan was one month old. Karachi was its mushrooming capital. On the sandy fringes of the city an enormous tent colony had grown up to house the influx of minor government officials. There was only one major government official, Mahomed Ali Jinnah, and there was no need for Jinnah to take to a tent. The huge marble and sandstone Government House, vacated by British officialdom, was waiting. The Quaid-i-Azam moved in, with his sister, Fatima, as hostess. Mr. Jinnah had put on what his critics called his "triple crown": he had made himself Governor-General; he was retaining the presidency of the Muslim League -- now Pakistan's only political party; and he was president of the country's lawmaking body, the Constituent Assembly.

"We never expected to get it so soon," Miss Fatima said when I called. "We never expected to get it in our lifetimes."

If Fatima's reaction was a glow of family pride, her brother's was a fever of ecstasy. Jinnah's deep-sunk eyes were pinpoints of excitement. His whole manner indicated that an almost overwhelming exaltation was racing through his veins. I had murmured some words of congratulation on his achievement in creating the world's largest Islamic nation.

"Oh, it's not just the largest Islamic nation. Pakistan is the fifth-largest nation in the world!"

The note of personal triumph was so unmistakable that I wondered how much thought he gave to the human cost: more Muslim lives had been sacrificed to create the new Muslim homeland than America, for example, had lost during the entire second World War. I hoped he had a constructive plan for the seventy million citizens of Pakistan. What kind of constitution did he intend to draw up?

"Of course it will be a democratic constitution; Islam is a democratic religion."

I ventured to suggest that the term "democracy" was often loosely used these days. Could he define what he had in mind?

"Democracy is not just a new thing we are learning," said Jinnah. "It is in our blood. We have always had our system of zakat -- our obligation to the poor."

This confusion of democracy with charity troubled me. I begged him to be more specific.

"Our Islamic ideas have been based on democracy and social justice since the thirteenth century."

This mention of the thirteenth century troubled me still more. Pakistan has other relics of the Middle Ages besides "social justice" -- the remnants of a feudal land system, for one. What would the new constitution do about that? .. "The land belongs to the God," says the Koran. This would need clarification in the constitution. Presumably Jinnah, the lawyer, would be just the person to correlate the "true Islamic principles" one heard so much about in Pakistan with the new nation's laws. But all he would tell me was that the constitution would be democratic because "the soil is perfectly fertile for democracy."

What plans did he have for the industrial development of the country? Did he hope to enlist technical or financial assistance from America?

"America needs Pakistan more than Pakistan needs America," was Jinnah's reply. "Pakistan is the pivot of the world, as we are placed" -- he revolved his long forefinger in bony circles -- "the frontier on which the future position of the world revolves." He leaned toward me, dropping his voice to a confidential note. "Russia," confided Mr. Jinnah, "is not so very far away."

This had a familiar ring. In Jinnah's mind this brave new nation had no other claim on American friendship than this - that across a wild tumble of roadless mountain ranges lay the land of the BoIsheviks. I wondered whether the Quaid-i-Azam considered his new state only as an armored buffer between opposing major powers. He was stressing America's military interest in other parts of the world. "America is now awakened," he said with a satisfied smile. Since the United States was now bolstering up Greece and Turkey, she should be much more interested in pouring money and arms into Pakistan. "If Russia walks in here," he concluded, "the whole world is menaced."

In the weeks to come I was to hear the Quaid-i-Azam's thesis echoed by government officials throughout Pakistan. "Surely America will build up our army," they would say to me. "Surely America will give us loans to keep Russia from walking in." But when I asked whether there were any signs of Russian infiltration, they would reply almost sadly, as though sorry not to be able to make more of the argument. "No, Russia has shown no signs of being interested in Pakistan."

This hope of tapping the U. S. Treasury was voiced so persistently that one wondered whether the purpose was to bolster the world against Bolshevism or to bolster Pakistan's own uncertain position as a new political entity. Actually, I think, it was more nearly related to the even more significant bankruptcy of ideas in the new Muslim state -- a nation drawing its spurious warmth from the embers of an antique religious fanaticism, fanned into a new blaze.

Jinnah's most frequently used technique in the struggle for his new nation had been the playing of opponent against opponent. Evidently this technique was now to be extended into foreign policy. ....

No one would have been more astonished than Jinnah if he could have foreseen thirty or forty years earlier that anyone would ever speak of him as a "savior of Islam." In those days any talk of religion brought a cynical smile. He condemned those who talked in terms of religious rivalries, and in the stirring period when the crusade for freedom began sweeping the country he was hailed as "the embodied symbol of Hindu-Muslim unity." The gifted Congresswoman, Mrs. Naidu, one of Jinnah's closest friends, wrote poems extolling his role as the great unifier in the fight for independence. "Perchance it is written in the book of the future," ran one of her tributes, "that he, in some terrible crisis of our national struggle, will pass into immortality" as the hero of "the Indian liberation."

In the "terrible crisis," Mahomed Ali Jinnah was to pass into immortality, not as the ambassador of unity, but as the deliberate apostle of discord. What caused this spectacular renunciation of the concept of a united India, to which he had dedicated the greater part of his life? No one knows exactly. The immediate occasion for the break, in the mid-thirties, was his opposition to Gandhi's civil disobedience program. Nehru says that Jinnah "disliked the crowds of ill-dressed people who filled the Congress" and was not at home with the new spirit rising among the common people under Gandhi's magnetic leadership. Others say it was against his legal conscience to accept Gandhi's program. One thing is certain: the break with Gandhi, Nehru, and the other Congress leaders was not caused by any Hindu-Muslim issue.

In any case, Jinnah revived the moribund Muslim League in 1936 after it had dragged through an anemic thirty years' existence, and took to the religious soapbox. He began dinning into the ears of millions of Muslims the claim that they were downtrodden solely because of Hindu domination. During the years directly preceding this move on his part, an unprecedented degree of unity had developed between Muslims and Hindus in their struggle for independence from the British Raj. The British feared this unity, and used their divide-and-rule tactics to disrupt it. Certain highly placed Indians also feared unity, dreading a popular movement which would threaten their special position. Then another decisive factor arose. Although Hindus had always been ahead of Muslims in the industrial sphere, the great Muslim feudal landlords now had aspirations toward industry. From these wealthy Muslims, who resented the well-established Hindu competition, Jinnah drew his powerful supporters. One wonders whether Jinnah was fighting to free downtrodden Muslims from domination or merely to gain an earmarked area, free from competition, for this small and wealthy clan.

The trend of events in Pakistan would support the theory that Jinnah carried the banner of the Muslim landed aristocracy, rather than that of the Muslim masses he claimed to champion. There was no hint of personal material gain in this. Jinnah was known to be personally incorruptible, a virtue which gave him a great strength with both poor and rich. The drive for personal wealth played no part in his politics. It was a drive for power. ......

Less than three months after Pakistan became a nation, Jinnah's Olympian assurance had strangely withered. His altered condition was not made public. "The Quaid-i-Azam has a bad cold" was the answer given to inquiries.

Only those closest to him knew that the "cold" was accompanied by paralyzing inability to make even the smallest decisions, by sullen silences striped with outbursts of irritation, by a spiritual numbness concealing something close to panic underneath. I knew it only because I spent most of this trying period at Government House, attempting to take a new portrait of Jinnah for a Life cover.

The Quaid-i-Azam was still revered as a messiah and deliverer by most of his people. But the "Great Leader" himself could not fail to know that all was not well in his new creation, the nation; the nation that his critics referred to as the "House that Jinnah built." The separation from the main body of India had been in many ways an unrealistic one. Pakistan raised 75 per cent of the world's jute supply; the processing mills were all in India. Pakistan raised one third of the cotton of India, but it had only one thirtieth of the cotton mills. Although it produced the bulk of Indian skins and hides, all the leather tanneries were in South India. The new state had no paper mills, few iron foundries. Rail and road facilities, insufficient at best, were still choked with refugees. Pakistan has a superbly fertile soil, and its outstanding advantage is self-sufficiency in food, but this was threatened by the never-ending flood of refugees who continued pouring in long after the peak of the religious wars had passed.

With his burning devotion to his separate Islamic nation, Jinnah had taken all these formidable obstacles in his stride. But the blow that finally broke his spirit struck at the very name of Pakistan. While the literal meaning of the name is "Land of the Pure," the word is a compound of initial letters of the Muslim majority provinces which Jinnah had expected to incorporate: P for the Punjab, A for the Afghans' area on the Northwest Frontier, S for Sind, -tan for Baluchistan. But the K was missing.

Kashmir, India's largest princely state, despite its 77 per cent Muslim population, had not fallen into the arms of Pakistan by the sheer weight of religious majority. Kashmir had acceded to India, and although it was now the scene of an undeclared war between the two nations, the fitting of the K into Pakistan was left in doubt. With the beginning of this torturing anxiety over Kashmir, the Quaid-i-Azam's siege of bad colds began, and then his dismaying withdrawal into himself. ....

Later, reflecting on what I had seen, I decided that this desperation was due to causes far deeper than anxiety over Pakistan's territorial and economic difficulties. I think that the tortured appearance of Mr. Jinnah was an indication that, in these final months of his life, he was adding up his own balance sheet. Analytical, brilliant, and no bigot, he knew what he had done. Like Doctor Faustus, he had made a bargain from which he could never be free. During the heat of the struggle he had been willing to call on all the devilish forces of superstition, and now that his new nation had been achieved the bigots were in the position of authority. The leaders of orthodoxy and a few "old families" had the final word and, to perpetuate their power, were seeing to it that the people were held in the deadening grip of religious superstition.

- Excerpts Copyrights: Simon & Schuster, 1949 / Margaret Bourke-White

- Photograph Copyrights: Time Inc., LIFE photo archive hosted by Google / Margaret Bourke-White

![Men adding wood & straw to funeral pyres in preparation for cremation of many corpses after bloody rioting between Hindus and Muslims[4] Men adding wood & straw to funeral pyres in preparation for cremation of many corpses after bloody rioting between Hindus and Muslims[4]](http://lh3.ggpht.com/-brHZS2b7DdU/USczKOHD_wI/AAAAAAAAC5Q/MBq8NOeNl_I/Men%252520adding%252520wood%252520%252526%252520straw%252520to%252520funeral%252520pyres%252520in%252520preparation%252520for%252520cremation%252520of%252520many%252520corpses%252520after%252520bloody%252520rioting%252520between%252520Hindus%252520and%252520Muslims%25255B4%25255D_thumb%25255B4%25255D.jpg?imgmax=800)

![Vultures feeding on corpses lying abandoned in alleyway after bloody rioting between Hindus and Muslims[5] Vultures feeding on corpses lying abandoned in alleyway after bloody rioting between Hindus and Muslims[5]](http://lh4.ggpht.com/-BcjMH2AKT7k/USczWluqwkI/AAAAAAAAC5g/TUdrpUQXS_Y/Vultures%252520feeding%252520on%252520corpses%252520lying%252520abandoned%252520in%252520alleyway%252520after%252520bloody%252520rioting%252520between%252520Hindus%252520and%252520Muslims%25255B5%25255D_thumb%25255B4%25255D.jpg?imgmax=800)

![Evacuees streaming across the Howrah Bridge on their way to the railway station in hopes of escaping the city after bloody rioting between Hindus and Muslims[3] Evacuees streaming across the Howrah Bridge on their way to the railway station in hopes of escaping the city after bloody rioting between Hindus and Muslims[3]](http://lh3.ggpht.com/-nsG8J5lsxlI/USczfdBKwFI/AAAAAAAAC5w/lr7Cjf_rlWM/Evacuees%252520streaming%252520across%252520the%252520%25255B8%25255D.jpg?imgmax=800)

![People waiting in railroad station trying to escape city after bloody rioting between Hindus and Muslims[3] People waiting in railroad station trying to escape city after bloody rioting between Hindus and Muslims[3]](http://lh4.ggpht.com/-LLicq8cfbrA/USczoqn2uLI/AAAAAAAAC6A/3svHpcgYdCE/People%252520waiting%252520in%252520railroad%252520station%252520trying%252520to%252520escape%252520city%252520after%252520bloody%252520rioting%252520between%252520Hindus%252520and%252520Muslims%25255B3%25255D_thumb%25255B5%25255D.jpg?imgmax=800)